Why God won’t go away?

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

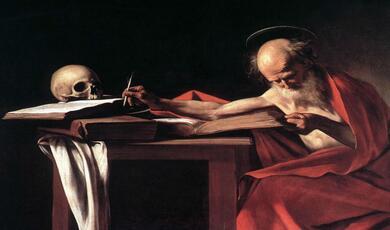

This concluding lecture considers a leading theme of Christian theology – that we have some innate tendency to believe in God (e.g., Pascal, George Herbert, and C. S. Lewis). The lecture then considers the evidence from recent "evolutionary cognitive science of religion" that religion is natural. The lecture assesses these findings, and considers their implications for debates about the future of religion in western culture.

Download Text

10 May 2016

Why God won’t Go Away

Professor Alister McGrath

Whether you think Christianity is right or wrong, there is no getting away from one of its core ideas – that human beings are in some way hard-wired to think about, even long for, God. It an idea that is set out in the opening paragraph of what is now increasingly regarded as the most important theological text in western Christianity: Augustine of Hippo’s Confessions, written between 397 and 400. Here’s the prayer in which Augustine sets out this idea: ‘You have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless until they find their rest in you.’

This idea of a ‘natural desire for God’ has been developed in all sorts of ways within the Christian tradition – such as Pascal’s idea of a God-shaped ‘abyss’ within human nature, which is too deep to be satisfied by anything less than God, or C. S. Lewis’s idea of a deep sense of yearning for significance, which both originates from and leads back to God. But the basic idea is simple: belief in God, like the phenomenon of religion itself, is natural. The Christian narrative tells us about a natural desire for God; a scientific narrative tells us about a desire for God that is natural. It is not difficult to see how these narratives can be interwoven at this point.

The rise of the ‘Age of Reason’ saw this view challenged in a number of ways. Many argued that religion was imposed upon people. Far from being something natural, it was something that was demanded of us by our culture, or which arose from pressures of social conformity. Yet there are now strong indications that religion is something natural. That doesn’t make it right or wrong. Where rationalism held that religion arose through the ‘sleep of reason’ – in other words, through the suspension of normal human critical and rational faculties – there is now a growing consensus that religion is best understood as a natural phenomenon, a cognitively natural human activity which arises through – not in spite of – natural human ways of thinking.

There are many fascinating questions that need to be explored arising from this recognition of natural religious tendencies. First, suppose that we grant that religious beliefs arise naturally in human cognitive development. Is this good news or bad news for theism or atheism? The jury’s out on this one, although I personally think that it works more in theism’s favour. Second, does a natural inclination towards religion imply that theism is natural? After all, ‘religion’ takes many forms (it’s not an empirical notion), and theism is one of them. Some would say that polytheism is the most natural outcome of the kind of process that the Cognitive Science of Religion addresses. And third, how do people move from this ‘natural religion’ to a specific religious tradition – for example, Christianity?

The empirical discipline which has explored this topic is a relatively new arrival on the scene. The term ‘cognitive science of religion’, introduced by the Oxford scholar Justin Barrett (born 1971), has come to designate approaches to the study of religion that are derived from the cognitive sciences. This approach brings theories from the cognitive sciences to bear on the question of why religious thought and action is so common in humans, and why religious phenomena have their observed forms. Setting the metaphysical claims of religion to one side, what is observed as ‘religion’ can be regarded as a complex amalgam of essentially human phenomena, which are communicated and regulated by natural human perception and cognition.

One of the basic empirical findings of this school of thought is that religion arises through normal processes of thought, not in opposition to these. It’s a natural aspect of being human, whether it’s right or wrong. Religion is natural, in that arises from human cognitive processes that are automatic, unconscious, and not dependent on culture. So let us look at this discipline in more detail, before going on to reflect on its implications.

Religion is here treated as a natural phenomenon, which arises through – not in spite of – natural human ways of thinking. This represents a significant challenge to some ways of evaluating religion, often inspired by the agenda of Enlightenment rationalism, which held that religion arose through the ‘sleep of reason’ – in other words, through the suspension of normal human critical and rational faculties.

The cognitive science of religion argues that it does not require a rigorous definition of ‘religion’ in order to proceed. Indeed, some would argue that the emergence of this new cognitive approach religion was motivated by dissatisfaction with the vagueness of previous theories of religion, and their inability to be empirically tested. As Justin Barrett notes, rather than specify what religion is and try to explain it in whole, scholars in this field have generally chosen to approach ‘religion’ in an incremental, piecemeal fashion, identifying human thought or behavioral patterns that might count as ‘religious’ and then trying to explain why those patterns are cross-culturally recurrent. If the explanations turn out to be part of a grander explanation of ‘religion’, then that is great. If not, at least meaningful human phenomena have still been rigorously addressed.

A further element of importance is the recognition that religion is not primarily about what might be termed ‘theological’ notions – such as the omnipotence of God, or the doctrine of the Trinity. Religious perceptions tend to be much simpler and more ‘natural’ than their theological counterparts. Whereas some have argued that religious beliefs are impositions upon human beings, the cognitive science of religion suggests that there are natural predispositions towards believing in God. A theme of particular importance in developing this stance is the notion of ‘minimally counterintuitive concepts’.

The cognitive anthropologist Pascal Boyer has argued religious beliefs belong to a class of ideas which could be called ‘minimally counterintuitive concepts.’ By this, he means that, on the one hand, they fulfil certain intuitive assumptions about any given class of objects (such as persons or objects), yet on the other hand violate some of those assumptions in ways which make the resulting concepts particularly exciting or memorable. In other words, religious notions are both plausible and memorable. They both belong to the everyday world, yet stand out from it. They are easily represented, and highly memorable. It is not quite clear, however, whether Boyer is arguing that counterintuitiveness is a universal characteristic of all religion, or whether it is simply a sufficient criterion for religion.

One obvious question concerns whether the ‘minimal counterintuitiveness’ approach to religious beliefs implies or entails the non-existence of the referents of these concepts and beliefs? While most cognitive scientists of religion state that this is not to be regarded an implication of the theory, it is clear that some scholars in the field (such as Scott Atran and Pascal Boyer) tend to imply that this ‘minimal counterintuitiveness’ theory of excludes or precludes a supernatural interpretation of the data, whereas others (such as Justin Barrett) hold that they do not. This raises a question that goes back to Sigmund Freud, whose precommitment to atheism famously led to his ‘explanations’ of religion: are cognitive scientists of religion allowing their worldviews to shape their interpretation of the data?

So how might Christian theology respond to the suggestion that we are predisposed to believe in God? For many theologians, this is simply a scientific description of what has long been held to be theologically true. The idea that humanity is inclined to quest for God is deeply embedded in many theological traditions. The biblical maxim that ‘You [God] have placed eternity in our hearts’ (Ecclesiastes 3:11) is one way of expressing this. Others might point to the famous prayer of Augustine of Hippo, which I noted earlier: ‘You have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in you’. There are clearly some intriguing possibilities for further exploration here.

And does the cognitive science of religion cast any light on the dialogue between science and religion? There are good reasons for thinking that this new discipline may help clarify this relationship. In an important recent study, Robert N. McCauley (Emory University) has argued that religious belief is natural. McCauley argues that a belief or action is to be thought of as ‘natural’ when it is ‘familiar, obvious, self-evident, intuitive, or held or done without reflection’ – in other words, when it ‘seems part of the normal course of events’.

Belief in God or supernatural agents therefore seems, McCauley argues, entirely natural. Yet he makes the important point that, when it comes to offering detailed explanations of what is believed about such supernatural agents, ways of thinking rapidly emerge which seem very unnatural. Although McCauley does not phrase it precisely in this way, his argument is basically that a basic belief in God or divine agency is much more natural than the theological descriptions which arise from this belief. In other words, the enterprise traditionally known as ‘systematic theology’ seems relatively unnatural, in that it involves a number of apparently counterintuitive steps. The doctrine of the Trinity would be a good example of a counterintuitive or ‘unnatural’ belief, which stands in contrast to a very natural belief in divine agency.

So what of the natural sciences? McCauley argues that, in certain ways, the natural sciences are experienced as unnatural, in that they involve methods, assumptions and outcomes which often – though by no means invariably – seem to be natural, in the sense of that which is ‘familiar, obvious, self-evident, intuitive, or held or done without reflection.’ McCauley illustrates this point in a number of ways, particularly by noting the counterintuitive character of innovative scientific theories.

Science challenges our intuitions and common-sense repeatedly. With the triumph of new theories, scientists and sometimes even the public must readjust their thinking. When first advanced, the suggestions that the earth moves, that microscopic organisms can kill human beings, and that solid objects are mostly empty space were no less contrary to intuition and common sense than the most counterintuitive consequences of quantum mechanics have proved for us in the twentieth century.

As McCauley suggests, the point will be familiar to any who have wrestled with the deeply counterintuitive notions of quantum mechanics. Yet even classical physical notions – such as the idea of ‘action at a distance’, which so troubled Isaac Newton – seem to contradict common sense.

Yet there is another level at which science appears to be unnatural. McCauley argues that the scientific enterprise demands extensive training and preparation, which often involved habits of thought and practice which seem some distance removed from the ordinary world. McCauley argues that institutionalized science involves forms of thought and types of practice that human beings find extremely difficult to master, and that scientific knowledge is not intuitive at all. After four centuries of astonishing accomplishment, McCauley suggests, science remains an overwhelmingly unfamiliar activity, even to most of the learned public and even in those cultures where its influence is substantial.

In suggesting that, in some respects, the natural sciences are ‘unnatural’, McCauley is not suggesting that they are wrong. He is simply making the point that they require developing certain ways of thinking which are not self-evidently true, and often seem to fly in the face of everyday experience or common sense. My own experience in learning about quantum theory in the 1970s strongly reinforces McCauley’s point. Counterintuitive notions such as entanglement and tunneling are easily dismissed as irrational, when they are just deeply counterintuitive.

So what are the implications of these ideas for the dialogue between science and religion? McCauley’s analysis suggests that the dialogue is not really between science and religion, but between science and theology. Both science and theology represent ways of thinking which are at least one step removed from the everyday and natural habits of thought which are typical of religion.

The field of the cognitive science of religion is relatively new, and this relatively brief discussion must be taken as a summary of work in progress. However, it seems very likely that the importance of this field will increase in coming decades, opening up some potentially important new discussions. For example, this cognitive approach to religion unquestionably helps us understand why religion is ubiquitous in human culture. Religion is so common within and across cultures because of its ‘cognitive naturalness’. C. S. Lewis may have overstated things when he suggested that the human search for meaning was as natural as sexual desire, or physical hunger and thirst. But you can see what he was getting at, and why the new cognitive approaches to the origins of religion reinforce his point. The origins of religious belief do not lie so much in cultural or social conditions, as in the intuitions that arise from normally developing and functioning human cognitive systems.

This strongly suggests that the secular humanist and ‘New Atheist’ visions for a totally secular human world are simply unrealistic, in that religion will naturally re-emerge, even where it is suppressed. It also suggests that non-religious people possess natural capacities and tendencies which might otherwise lead to religion, but which have either not yet been activated by any triggers in their environment or experience, or which have been suppressed by social or cultural pressures.

So why are we hardwired in this way? Nobody really knows, and it is tempting to present somewhat speculative ‘just-so’ stories as if they were genuine explanations. I’m afraid that some of the so-called ‘Darwinian’ explanations of the origins of religion fall into this category. The point we need to grasp here is that, before we can offer an evolutionary account of the origins of religion, we need to determine whether religion is biologically adaptive or not. There is no consensus on this matter at present. Some scholars argue that there is no obvious adaptive function to religion, while others hold that religion can clearly be understood in adaptationist terms. There is simply no scholarly consensus on this matter at present.

It is true that Richard Dawkins declares that religion is non-adaptive, and damages people. If religious beliefs are adaptive in any sense, he insists, it is only in that they act successfully as cultural parasites within their human hosts. Yet his analysis is conspicuously lacking in empirical engagement of any kind, and runs counter to many other evolutionary biologists, who take a very different view – such as David Sloan Wilson.

Now let us change direction, and get back to the topic of this lecture. Will the idea of God go away? I think not, and we’ve explored some reasons for this. Now I have already noted C. S. Lewis in this lecture, and it seems appropriate to ask how Lewis engages this theme of ‘desire for God’. For a start, this allows us to make some connections with some of the points we have just explored. It will also allow us to open up some deeper questions, and I will do this later in this lecture. Let’s look at Lewis himself to begin with.

The starting point for Lewis’s approach is an experience – a longing for something undefined and possibly undefinable, that is as insatiable as it is elusive. Lewis sets out versions of this argument at several points in his writings, including the ‘Chronicles of Narnia’. The most important statements of the argument, however, are the following:

1. The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933), written shortly after his conversion to Christianity, in which Lewis sets out an allegorical account of his own conversion, focusing on the theme of desire.

2. The university sermon ‘The Weight of Glory’, preached in Oxford in June 1941, and subsequently published as an article in the journal Theology. This is the most elegant statement of the argument, which is here framed primarily in terms of the human quest for beauty.

3. The talk ‘Hope’, given during the third series of Broadcast Talks for the British Broadcasting Corporation during the Second World War, and subsequently reproduced as a chapter in Mere Christianity. This is generally considered to be Lewis’s most influential statement of the argument.

4. The autobiographical work Surprised by Joy, in which the theme of ‘Joy’ plays a significant role in arousing Lewis’s openness towards God.

In Surprised by Joy, Lewis described his childhood experiences of intense longing (which he names ‘Joy’) for something unknown and elusive, triggered off by such things as the fragrance of a flowering currant bush in the garden of his childhood home in Belfast, or reading Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem in the style of the Swedish poet Esaias Tegnér. Lewis’s epiphany of ‘Joy’ bathed his everyday world of experience with beauty and wonder. But what did it mean – if it meant anything at all? What way of seeing it might help him to make sense of it? How was he to interpret it?

While an atheist, Lewis dismissed such experiences as illusory. Yet he became increasingly dissatisfied with such simplistic reductive explanations. His growing familiarity with what he termed the ‘Christian mythology’ – Lewis here uses the term ‘myth’ in the sense of a ‘narrated worldview’ – led him to appreciate that these experiences could easily and naturally be accommodated within its explanatory framework. What if God were an active questing personal agent, as Christianity affirmed to be the case? If so, God could easily be understood as the ‘source from which those arrows of Joy had been shot at me ever since childhood.’

In the sermon ‘The Weight of Glory’, Lewis develops this theme further by exploring the human quest for beauty. Lewis argues that this is really a search for the source of that beauty, which is mediated through the things of this world, but not contained within them. ‘The books of the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them: it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing.’ Without a Christian way of seeing things, this longing remains ‘uncertain of its object’. Its true goal remains to be identified and attained.

Christianity, Lewis declares, gives us the intellectual framework that both interprets the experience, and leads us to its true goal. In his own way, Lewis reworks the point so famously made by T. S. Eliot in Dry Salvages:

We had the experience but missed the meaning;

And approach to the meaning restores the experience.

In Mere Christianity, Lewis sets out this approach in a somewhat different way, while still appealing to the elusiveness of our experiences of ‘Joy’. The experiences he had in mind are shared across the human spectrum, often expressed in quotidian language as a sense of there being ‘something there’. The great Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky, for example, spoke of ‘a nostalgic yearning, bordering at times on unendurably poignant sorrow’, which he experienced in ‘the dreams of my heart and in the reveries of my soul.’ Bertrand Russell, one of the most articulate and influential British atheist writers of the twentieth century, put a similar thought into words as follows:

The centre of me is always and eternally a terrible pain . . . a searching for something beyond what the world contains, something transfigured and infinite – the beatific vision, God – I do not find it, I do not think it is to be found – but the love of it is my life . . . it is the actual spring of life within me.

Russell’s daughter, Katharine Tait, recalled that he was contemptuous of organized religion, dismissing its ideas mainly because he disliked those who held them. Yet Tait took the view that her father’s life was really an unacknowledged, perhaps disguised, search for God. ‘Somewhere at the back of my father’s mind, at the bottom of his heart, in the depths of his soul, there was an empty space that had once been filled by God, and he never found anything else to put in it.’ Russell was now haunted by a ‘ghost-like feeling of not belonging in this world.’

These are the kinds of experience to which Lewis appeals – a sense of hovering on the brink of discovering something of immense significance, linked with a sense of sorrow and frustration when what seemed to be so close tantalizingly disappears. Like smoke, it cannot be grasped. As Lewis puts it: ‘There was something we grasped at, in that first moment of longing, which just fades away in the reality.’ So what does this sense of unfulfilled longing mean? To what does it point?

Some, Lewis concedes, might suggest that this frustration arises from looking for its true object in the wrong places; others that, since further searching will only result in repeated disappointment, there is simply no point trying to find something better than the present world.

Yet Lewis suggests that there is a third approach, which recognizes that these earthly longings are ‘only a kind of copy, or echo, or mirage’ of our true homeland. Since this overwhelming desire cannot be fulfilled through anything in the present world, this suggests that its ultimate object lies beyond the present world. ‘If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world’.

Here, as throughout his apologetic writings, the starting point of Lewis’s approach does not lie with the Bible or the Christian tradition, but with shared human experience and observation. How do we make sense of them? Lewis’s genius as an apologist lay in his ability to show how a ‘viewpoint’ which was derived from the Bible and the Christian tradition was able to offer a more satisfactory explanation of common human experience than its rivals – especially the atheism he had once himself espoused.

Lewis’s apologetic approach is to identify a common human observation or experience, and then show how it fits in, naturally and plausibly, within a Christian way of looking at things. For Lewis, Christianity provided a ‘big picture’, an intellectually capacious and imaginatively satisfying way of seeing things. Lewis was always emphatic that nothing can be proved on the basis of observation or experience. Yet while such observations of nature or our own experiences prove nothing, they can suggest certain possibilities, and even intimate what they might mean. That’s what Lewis is getting at when he writes:

A true philosophy may sometimes validate an experience of nature; an experience of nature cannot validate a philosophy. Nature will not verify any theological or metaphysical proposition (or not in the manner we are now considering); she will help to show what it means.

A similar approach is found in G. K. Chesterton, who once remarked that: ‘The phenomenon does not prove religion, but religion explains the phenomenon.’

Lewis’s approach could be framed like this. Christianity holds that the natural order – including our own reasoning – is shaped by the God who created all things. As Augustine of Hippo and Blaise Pascal had argued before him, Lewis affirms that the absence of God causes us to experience longing – a yearning for God, which we misinterpret as a longing for something located within the finite and created order. Conversion is thus partly about a semiotic transformation, in which we realize that something we believed to be pointing to one thing in fact points to something rather different.

We could set Lewis’s argument out more formally as follows. We experience desires that no experience in this world seems able to satisfy. Yet Christianity tells us that we are made for another world. And when things are seen in this way, this sort of experience is exactly what we would expect. The appeal is not so much to cold logic, as to intuition and imagination, resting on an imaginative dynamic of discovery. Lewis invites his audience to see their experiences through a set of Christian spectacles, and notice how these bring what might otherwise be fuzzy or blurred into sharp focus. For Lewis, the ability of the Christian faith to accommodate our experience, naturally and easily, is an indicator of its truth.

As Lewis states this approach from desire, therefore, it is not really an argument at all; it is more about observing and affirming the fit between a theory and observation. It is like trying on a hat or shirt for size. How well does it fit? How many of our observations of the world can it accommodate, and how persuasively? Lewis’s way of thinking also shows some similarity to a related approach within the natural sciences, now generally known as ‘inference to the best explanation’. This approach recognizes that there are multiple explanations of observations, and suggests how criteria might be identified to determine which such explanation is to be considered as ‘the best’.

The same approach is found in Lewis’s ‘argument from morality.’ This is sometimes portrayed in ridiculously simplistic terms – for example, ‘experiencing a sense of moral obligation proves there is a God.’ Lewis did not say this, and did not think this. As with the ‘argument from desire’, his argument is rather than the common human experience of a sense of moral obligation is easily and naturally accommodated within a Christian framework.

For Lewis, experiences and intuitions – for example, concerning morality and desire – are meant to ‘arouse our suspicions’ that there is indeed ‘Something which is directing the universe.’ We come to suspect that our moral experience suggests a ‘real law which we did not invent, and which we know we ought to obey’, in much the same way as our experience of desire is ‘a kind of copy, or echo, or mirage’ of another place, which is our true homeland. And as we track this suspicion, we begin to realize that it has considerable imaginative and explanatory potential. What was initially a dawning suspicion becomes solidified as a growing conviction that it makes sense of what matters to us naturally and persuasively.

So what can be learned from Lewis’s approach? Perhaps I could mention two points. First, Lewis helps us see that apologetics need not take the form of a slightly dull deductive argument, but can be understood and presented as an invitation to step into the Christian way of seeing things, and explore how things look when seen from its standpoint. ‘Try seeing things this way!’ If worldviews or metanarratives can be compared to lenses, which of them brings things into sharpest focus?

And second, we need to realize that Lewis’s explicit appeal to reason involves an implicit appeal to the imagination. Perhaps this helps us understand why Lewis appeals to both modern and postmodern people. I see no historical evidence that compels me to argue that Lewis deliberately set out to do this, constructing a mediating position between two very different cultural moods. The evidence suggests that he saw things this way naturally, and never formalized it in terms of a synthesis of these two very different modalities of thought. Lewis rather gives us a synoptikon which transcends the great divide between modernity and postmodernity, affirming the strengths of each, and subtly accommodating their weaknesses.

Yes, Lewis affirms the rationality of the universe – but does so without plunging us into an imaginatively drab world of cold logic and dreary argumentation. Yes, Lewis affirms the power of images and narratives to captivate our imagination – but does so without giving up on the primacy of truth.

Now there are many points at which Lewis’s approach could be challenged, and I certainly think that further discussion is needed at several points. Whether you think he’s right or not, though, I think he helps us to reflect on that point from T. S. Eliot that I quoted earlier, but will read again, as it is important:

We had the experience but missed the meaning;

And approach to the meaning restores the experience.

What Lewis does is provide a framework for making sense of our experiences. Yet the framework does more than interpret; it allows a new experience of experience (if you see what I am getting at). It enriches the quality of our experience, by forcing us to ask what it is that we are actually experiencing. Now that’s a fascinating topic in its own right!

But I can’t pursue it here. I want to end this lecture by opening up what some of you may consider to be a controversial question, but one which I think is well worth asking. We now know that it is natural to be religious. This does not make this right or wrong; nor does it imply that everyone is or ought to be religious. It is just noting that there are natural human instincts, intuitions and thought processes whose outcome tends to be religious in nature. It is deeply human to be religious.

So here is my controversial question. If it is natural for humans to be religious, why do we use the word ‘humanism’ to mean an anti-religious attitude or outlook? As some of you will know, one of my major research interests back in the 1980s focussed on a group of humanist writers based in Switzerland, including Joachim von Watt (Vadian), Johannes Xylotectus, and Heinrich Glarean. Although Renaissance humanism was characterized by no distinctive philosophical or ideological stance, the fact remains that, virtually without exception, Renaissance humanists were religiously-engaged Christians who saw themselves as operating within the context of the life and thought of the church, concerned for its reform and renewal. The Enlightenment tendency to portray the humanists as precursors of the Enlightenment critique of religion lacks plausibility, not least because leading humanists of the age – such as Pico della Mirandola, Lorenzo Valla, and above all Erasmus of Rotterdam – tended to see humanism as continuous with the medieval catholic spiritual tradition, rather as a precursor of rationalism. It is virtually impossible to read Erasmus’s explicitly religious works – such as the bestselling Handbook of the Christian Soldier (1503) – without noting his enthusiasm for religion, linked with a desire to reform corrupt religious institutions.

So what just what did the word ‘humanism’ mean in the Renaissance? It was fundamentally about the renewal of a moribund culture through the ‘revival of good letters.’ Secular culture could be renewed by a return to the classics of Greece and Rome. The church could be renewed by returning directly to the New Testament. The slogan ad fontes – back to the original sources! – can be seen as the watchword of this approach.

So how did this word come to mean an anti-religious movement? Actually, this turns out to be a relatively recent development, and is specifically linked with the United States. The American ‘Humanist Manifesto’ of 1933 made specific approving reference to religious humanism, recognizing that it was perfectly meaningful to talk about – for example – ‘Christian humanism’. However, the writer Paul Kurtz vigorously advocated more secular forms of humanism, and formed the ‘Council for Secular Humanism’ to lobby for a fundamental change in direction of the American Humanist Association. He was one of the two main authors of the ‘Humanist Manifesto II’ (1973), which set out a strongly secular vision for a form of humanism that was systematically evacuated of religious possibilities and affirmations, and founded the Center for Inquiry to promote this specific form of humanism.

Thanks to lazy and uncritical media reporting, Kurtz’s vision of secular humanism quickly became elided with humanism, and was read back into older visions and implementations of the movement – including the highly implausible and totally unevidenced belief that Renaissance humanism was an essentially atheistic movement. I don’t see how anyone could read Erasmus’s commentaries on the New Testament and come to that conclusion!

I am very happy to describe myself as a Christian humanist. That is only a contradiction in terms – what the Americans call an ‘oxymoron’ – if you think ‘humanism’ is intrinsically atheist. But that is a recent development, and we need to reverse it, and get back to an older and better way of thinking. I have no objection to anyone setting out a vision of secular humanism. My complaint is the exclusivity of this notion of humanism, which refuses to acknowledge the legitimacy of other visions of human nature, and understandings of human fulfilment.

Let me turn to the philosopher Mary Midgley, who clearly considers herself to be a non-theistic humanist. She makes the interesting and intriguing point that an aggressively anti-theistic humanism can pull the rug out from under itself. In an important essay entitled ‘The Paradox of Humanism’, Midgley points out the vulnerability of reductive forms of humanism, which eliminate the transcendent in the mistaken belief that this safeguards the human.

Humanism, Midgley argues, exists to ‘celebrate and increase the glory of human life’, without having to express any devotion towards any entities outside it – such as God. But as soon as anyone starts to eliminate those entities, ‘valuable elements in human life’ begin to unravel. ‘The center begins to bleed.’ Why? Because the ‘patterns essential to human life turn out to be ones that cannot be altogether contained within it.’ As Midgley puts it, ‘to be fully human seems to involve being interested in other things as well as human ones, and sometimes more than human ones.’

Well, there is some food for thought! But I must end without resolving these issues, and leave you space to think through your own views on these matters. And I must also end by telling you what I hope to do next academic year. As you know, we shall be moving these lectures to a larger lecture room, which I hope will mean that I can see you all! My topic is going to be this: Religion, Science, and Culture: Six Big Questions. I’m going to reflect with you on six questions that are really interesting. And to make them more interesting, I am going to engage in respectful dialogue with another voice – sometimes someone who I agree with, sometimes someone who takes a very different perspective. And I hope that this will make for a really interesting lecture. Here is what we will be doing:

Lecture 1: Does science rob nature of its mystery and beauty? And does theology restore this? John Ruskin on science, religion, and the arts

Lecture 2: Does faith make sense of things? Dorothy L. Sayers on science, faith, and the quest for intellectual order

Lecture 3: Is reality limited to what science can uncover? C. S. Lewis’s critique of naturalism.

Lecture 4: Respecting and Transcending Nature: J. R. R. Tolkien’s concerns about technology

Lecture 5: Is humanity naturally good? Richard Dawkins’s Selfish Gene

Lecture 6: Is matter evil? Philip Pullman’s Dark Materials trilogy

I hope that you will feel that my choice of topics and dialogue partners is interesting! It just remains for me to thank you for being such a patient and tolerant audience, and to tell you how much I look forward to seeing you again in the autumn.

© Professor Alister McGrath, 2016

This event was on Tue, 10 May 2016

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login